Āvartan – आवर्तन

Quick Definition: One cycle, or round, of a tal.

Literal Meaning: rhythm; round; rotation

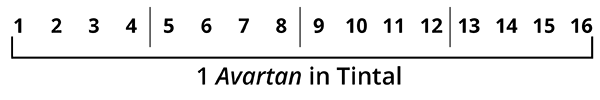

Example Avartan

About Avartan

An avartan is the full cycle of any tal. So in tintal, which has 16 matras (beats), one avartan will be 16 matras long. In rupak tal (7 matras) one avartan will be seven matras.

Similar to the sam (the first matra of the tal), the avartan often has an important role in performance. Musicians need to be aware of where they are in the avartan, for example. They also sometimes need to be aware of how many avartans they will play for. For tabla players especially, this is a regular part of practice.

Avartan Awareness

In accompaniment, tabla players might decide to improvise for a particular number of avartans. This could be for a variety of reasons, such as matching something that the soloist plays. Or he might choose to play a short or long improvisation to match the mood or flow of the music at that moment.

Avartan awareness is also important in the mathematics of performance. Tabla players regularly use basic mathematics to calculate how many beats it will take to get from point A to point B. Point A could be from anywhere in the avartan, and point B is usually the sam.

For example, long tihais or chakradars can last for 4 or 5 avartans or more. Tabla players with good avartan awareness will be able to tell exactly where to start from, and how many avartans a particular pattern will last.

The Avartan and Sam

As discussed in the previous section, most compositions and improvisations will finish on sam, the first matra of the avartan. This means that they will overlap with a new avartan.

So musician will often think in terms of a certain number of avartans "plus one", to make sure that they finish on sam.

This might seem like a small point, but it is one that musicians have to think about regularly. And it is an important part of the mathematics that classical Indian musician often use when they play.

For example, if a tabla player wants to improvise a tukra or mukhra which begins on sam and lasts for two avartans of tintal (a 16-matra cycle), he knows that he must play for 33 matras, not 32: 2 x 16 = 32 + 1 = 33.

If he wants to play something which lasts for 4 avartans, he will play for 65 matras: 4 x 16 = 64 + 1 = 65.

And because most cadential forms (tihai, tukra, chakradar, paran, etc.) are irregular in their structure—meaning that they don’t follow the form of the tal—they can go on for many avartans before coming back to the one.

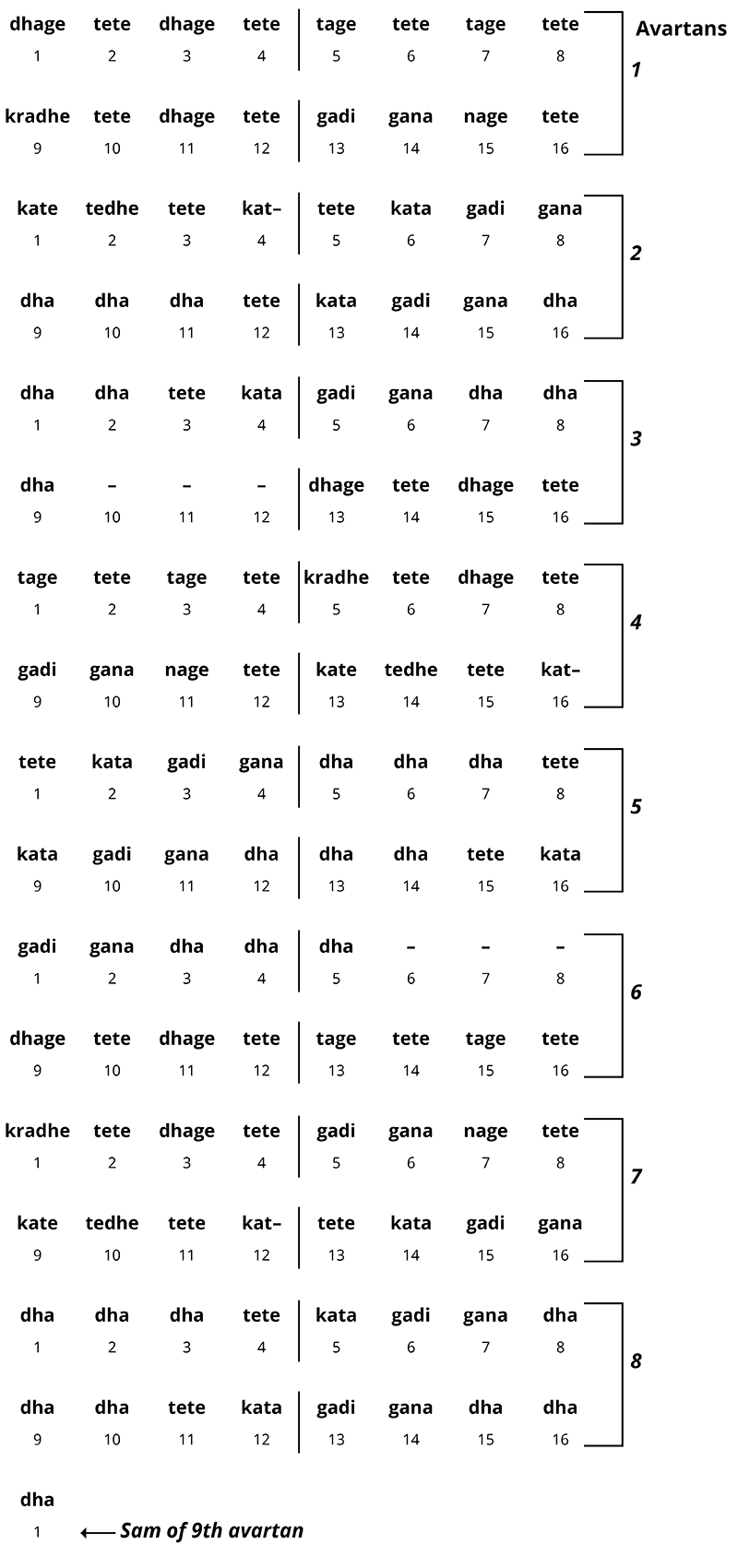

Below is a paran which which has a chakradar form. It lasts for eight avartans plus one, ending on sam of the 9th avartan. It is 129 matras long (16 x 8 = 128 + 1 = 129):

(from Benares Paran 2)

Even in long compositions such as this, tabla players will always know where they in the avartan.

Conclusion of Tal

Avartan is the last of the 5 elements of tal (matra, vibhag, tali-khali, and sam are the other 4).

As I will keep saying, for listeners, tal may be the single most important thing to learn about classical Indian music and classical tabla. If you are not grounded in the tal, then you will not be able to follow much of the music.

After you learn the basics of tal, there are two other important areas of the music which will help you follow and understand a performance: lay (tempo) and layakari (division of the beats).