Tāl – ताल

Quick Definition: A rhythmic cycle. Tāl (or tālī) may also express its literal meaning of "clap".

Literal Meaning: clap; rhythm; measure

(Note: These sections are about the structure and theory of tal. For examples of particular tals, see the Tals and Thekas section.)

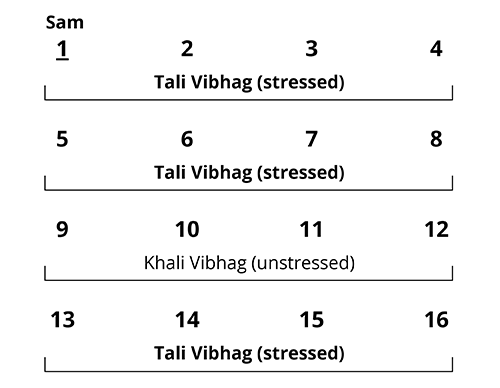

Example Tal: Tintal

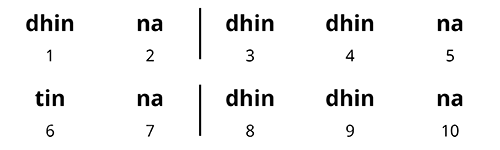

16-beat tal divided into 4 sections of 4 beats:

Introduction to Tal

If you are a new listener and you only learn one thing about classical Indian music, understanding tal may be the most helpful. This is because most of Northern classical Indian music, and all of classical tabla, is performed within tal. And if you can’t follow the tal, then you can’t follow much of the music.

In English, tal is most often described as a "rhythmic cycle": a fixed number of beats that goes around and around. But a tal is more complex than a simple cycle. Every tal has a particular structure, including divisions and stress.

In the video above, we see the structure of tintal, a 16-beat cycle with 4 divisions of 4 beats. Each division’s stress or non-stress is shown with a clap or a wave (more on this below).

This basic structure is not difficult to learn for the most common tals. The difficulty for new listeners is following the tal in performance.

It’s difficult because we often don’t hear a tal’s structure in the music, and we don’t always feel tal as a rhythm or groove.

But with some guidance, you can quickly learn to follow some simple compositions and performances. And little by little, with practice, the music will start to make more sense.

About the Sections on Tal

If you just want a basic introduction to tal, this page should be enough. But if you’re serious about listening to classical tabla, I suggest that you learn more about the five elements of tal. They are introduced below, and then discussed in more detail in the following sections.

I also suggest you learn to keep time with the hands for at least tintal (more on this below).

For people who want to know more about the theory of tal and Indian meter in general, I recommend Time in Indian Music: Rhythm, Metre, and Form in North Indian Rāg Performance by Martin Clayton. This book was the primary source for clarifying many of my own confusions about the theory of tal.

Common Tals of Northern Classical Indian Music

There are many different tals in both Northern and Southern classical Indian music. Some scholars have listed hundreds. However, most of these are rarely performed.

Currently, there are about 15–20 tals that are commonly performed in the northern Hindustani tradition. And the following 6 tals are the most common in modern performance:

- Tintal: 16-beats

- Rupak Tal: 7-beats

- Jhaptal: 10-beats

- Ektal: 12-beats

- Kaharawa Tal: 8-beats (light classical)

- Dadra Tal: 6-beats (light classical)

(See the extended list of tals for tals not mentioned here.)

Tintal is the dominant tal, especially for tabla. The majority of all tabla compositions have been composed in tintal, or have been adapted from tintal to other tals.

While tals may differ greatly in their lengths and structures, they all share the same general characteristics.

The Five Elements of Tal

There are 5 elements of tal which we will look at in the following sections. For now, here are basic descriptions of each, followed by some example tal structures further below:

- Mātrā: These are the beats, or pulses, in a tal. Every tal has a fixed number of mātrās (16, 10, 7, etc.).

- Vibhāg: The matras in every tal are divided into sections called vibhāg. For example, the 16-matra cycle of tintal has four vibhags of four matras each (4–4–4–4).

- Tālī-Khālī: Every vibhag in a tal is either a tālī vibhag, or a khālī vibhag. Tali vibhags are stressed and shown by a clap. Khali vibhags are unstressed and shown by a wave.

- Sam: The sam is the first matra of a tal. It is both the end of one cycle and the beginning of the next. Sam is often a point of resolution, where many improvisations and compositions will end.

- Āvartan: The āvartan is the full cycle of any tal. One avartan in tintal (a 16-matra cycle) is 16 matras long. One avartan in jhaptal (a 10-matra cycle) is 10 matras long. Etc.

A tal’s structure can be shown with the hands

Musicians will often show the structure of the tal using a pattern of claps and waves, as in the video at the beginning of this section. This is known as keeping time.

This is an ancient practice and explains the origins of the word tal, meaning “clap.”

We’ll look at some timekeeping examples below. For more information, see the Keeping Time section.

Example Tal Structures

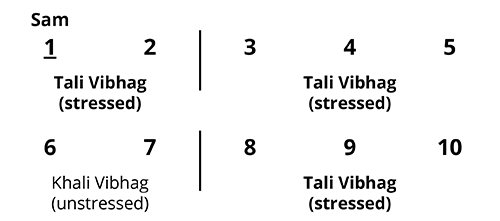

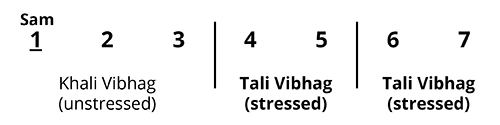

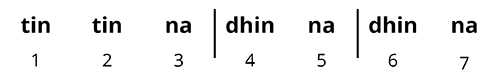

Below we can see these five elements of tal in the structures of tintal, jhaptal, and rupak tal. For each tal, we see 1 written avartan, or cycle.

The videos show the timekeeping pattern for each tal. Here two avartans are given.

Tintal Structure (16 matras):

Jhaptal Structure (10 matras):

Rupak Tal Structure (7 matras):

You can learn more about these and other tals in the Tals and Thekas section.

Tals are associated with thekas

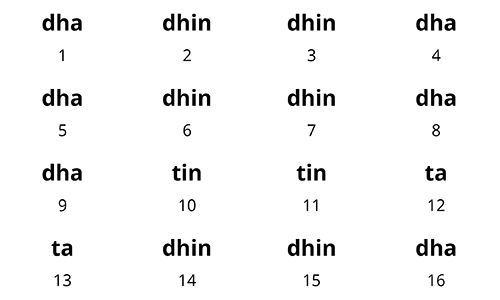

When we think of a tal, we often think of the theka for that tal. A theka is a kind of base composition for a particular tal, heard most often in accompaniment.

But the theka is not the tal itself; the theka is a composition composed in a tal, and its main job is to show the tal.

For this reason, thekas are strongly associated with tals. And learning the theka is how most students and listeners first learn to follow the tal.

Common Theka Examples

Below are the standard thekas for the three tals introduced above:

Tintal Theka (16 matra cycle)

Tintal Theka Demonstration (played 4 times):

Jhaptal Theka (10 matra cycle)

Jhaptal Theka Demonstration (played 4 times):

Rupak Tal Theka (7 matra cycle)

Rupak Tal Theka Demonstration (played 4 times):

Thekas and their relationship to tal are discussed in the description of Thekha, and in the Tals and Thekas section. However, I suggest that your first learn about the structure of tal in the following sections before moving on to thekas.

The Challenge of Following the Tal

For new listeners especially, following the tal can be a challenge. This is partly because the music does not always follow the structure of the tal; sometimes it does, sometimes it doesn’t. This is true on both sides of the music, melody and tabla.

Below are some examples of how tabla performance may, or may not, reflect the tal:

- Thekas follow the structure of the tal most consistently. That’s their job: to show us the tal. However, some thekas do this more clearly than others.

- Other cyclic forms such as the kayda and rela will usually share the tal’s structure, but they can change their speed and length, and so they are not always aligned with the tal’s structure.

- Many fixed/cadential compositions such as the tihai, tukra, and chakradar will not follow the structure of the tal at all, other than their overall length.

- When tabla players solo in accompaniment, they will often mix a variety of cyclic styles in unpredictable ways, sometimes aligning with the tal, sometimes not, and then finish with a tihai (a non-cyclic form) on sam, the first beat of the cycle.

With all this variation in performance, you can understand why learning to follow the tal is essential to listening and performance.

Tabla students, of course, will learn to follow the tal as part of their training.

For serious listeners, learning to keep time is the easiest and fastest way to learn how to follow the tal.

But you should also understand more about the structure of tal introduced above.

And to do that, the best place to start is the beat, or pulse, of the tal: the matra.

References

Clayton, Martin. Time in Indian Music: Rhythm, Metre, and Form in North Indian Rāg Performance. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Misra, Chhote Lal. Tal Prabandh. New Delhi: Kanishka Publishers, 2006. (Hindi)

Stewart, Rebecca Marie. The Tabla in Perspective. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, 1974.