Kayda Phrases

Introduction to Kayda Phrases

As we saw in the last section, the basic stress pattern of a kayda is easy to understand. And a simple kayda should be easy to follow.

But most kaydas are more complex, especially their phrases. And it is here that many new listeners get lost.

This is partly because tabla phrasing is so unique; until you are familiar with these phrases, a lot of classical tabla simply won’t make much sense.

The best way to learn kayda phrases, of course, is by learning to play. And if you are a tabla student, stop reading and go practice. Listeners, however, will need some guidance.

Though we won’t be looking at kayda phrases in depth in this section, we will look at some of their common characteristics. This should help you get oriented and have some idea of how to understand—and eventually hear—kaydas on your own.

In particular, we will look at:

- How a kayda’s theme is made from multiple main phrases

- How main phrases are made from smaller phrases and bols

- How individual bols help to create a kayda’s stress pattern

At the end of this section, there are some suggestions for learning kayda phrases in more depth.

Definitions of “Bol”, “Phrase”, and “Main Bol”

The terms “bol”, “phrase”, and “main bol” can be used in different ways. In this section, I will use them as follows to avoid confusion:

-

Bol refers to individual strokes, or small groups of strokes which do not create a percussive statement. This includes dha, dhin, tete, tirakita, dhati, dhagina etc.

-

Phrase refers to a combination of bols which creates a percussive statement. This could be a simple statement, such as dhadha tete. Or it could be longer, such as dha- kradha tidha gina dhati dhage dhinna gina. These can also be called bols, but here I will call them phrases.

-

Main Bol refers to the “parent composition” that we saw in the last section, and not necessarily the complete kayda theme.

The main bol is made from at least two main phrases

As we saw in the last section, every kayda is divided into two halves. And each half is a different version of the main bol, or the parent composition.

This main bol, in any kayda, is always made from at least two main phrases.

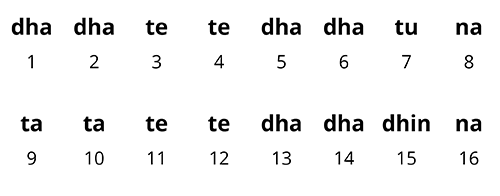

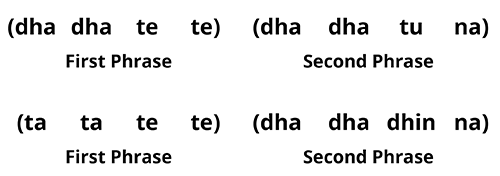

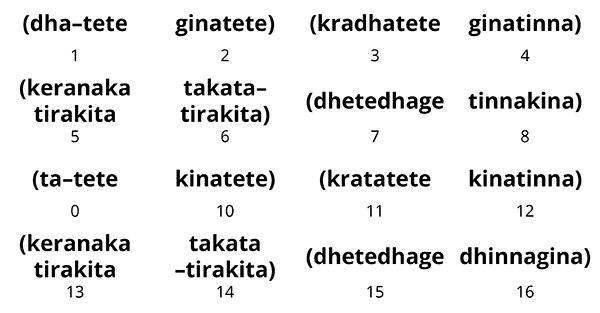

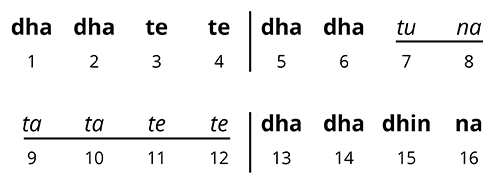

Here again is our beginner kayda:

The main bol is dhadha tete dhadha dhinna. And this is made from two main phrases:

- dhadha tete

- dhadha dhinna

So each half of the kayda is a different version of this combination:

Listen again to the theme and notice the simple contrast between the two main phrases in each half:

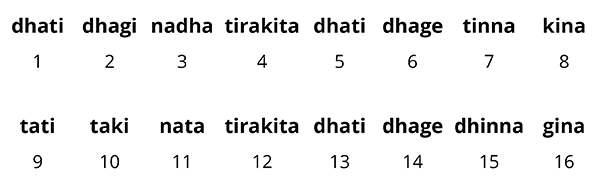

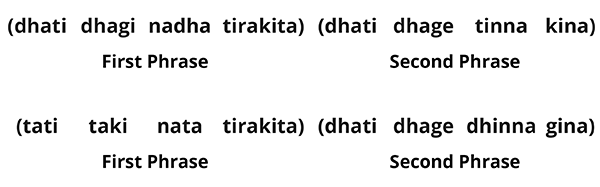

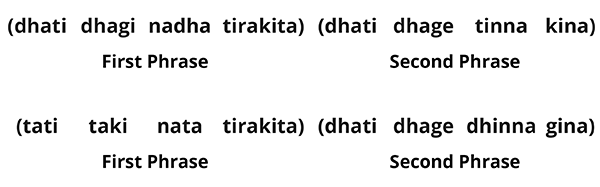

For another example, here is the Dilli kayda that we saw in the last section:

Here the main bol is:

- dhati dhagi nadha tirakita dhati dhage dhinna gina

And this has two main phrases:

- dhati dhagi nadha tirakita

- dhati dhage dhinna gina

Here too, each half is a different versions of the main bol:

These 2 phrases are more complex than the first kayda above. They are also less similar to each other. But like the first kayda, you should hear how they compliment each other:

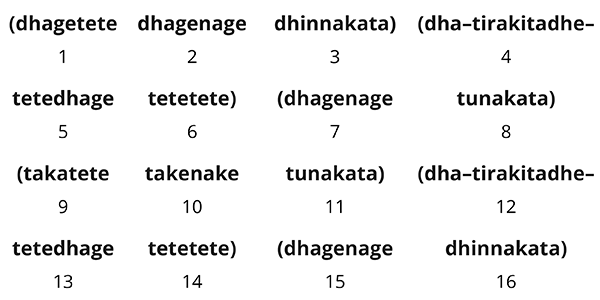

Below is Dilli kayda with 4 main phrases in each half. This kayda has more bols per matra and more vareity of phrases:

(from Dilli Kayda 5)

So every main bol has at least two main phrases. Next we’ll look at how each of these main phrases is made from smaller parts.

Main phrases are made from smaller bols

The main phrases in a kayda are always made from smaller bols. As I noted above, this is what makes a phrase: a combination of smaller bols which creates a percussive statement.

Even the main phrases of our simple beginner kayda have smaller parts. Dhadha tete is made from dhadha and tete, for example.

This may sound obvious, but it is often the smaller bols of the language—and how they connect with other bols—that are missed by new students and listeners. And as you will see, most kaydas are more complex than dhadha tete dhadha tuna.

For example, the Dilli kayda we saw above has two main phrases in each half and seems easy to understand. As written below, it appears to be a 4–4–4–4 pattern of 2 strokes per matra (matras 4 and 12 are double time):

However, the bols of the first phrase dhati dhagi nadha tirakita are not actually divided 2–2–2–2. They are only written this way to show us the matras. This phrase is actually made of three common bols divided 2–3–3:

- dhati (2)

- dhagina (3)

- dha-tirakita (3)

The second phrase has even divisions of 2-2-2-2:

- dhati (2)

- dhage (2)

- tinna (2)

- kina (2)

So the two main phrases together give us a pattern of 2–3–3 / 2–2–2–2.

Listen to this kayda again and see if you can follow these divisions in each half:

So the main phrases in a kayda are usually more complex than they may seem. And so far, the examples we have seen are relatively straightforward, with evenly divided main phrases (4–4–4–4 ). Things get even more complicated when the main phrases themselves have uneven lengths.

Not all tintal kaydas have four even phrases

All of the kaydas above, and many other kaydas in tintal, have four even main phrases which match the four vibhags (divisions) of tintal (4–4–4–4). However, there are also many kaydas with uneven phrase divisions.

For example, the kayda below could be divided into main-phrases of 3–3–2 in each half:

Notice also that the khali section (matras 9-11) is just 3 matras long. So the specific stress patterns of tintal kayda phrases do not always match the exact divisions of the tal. But the overall stress pattern will still generally reflect the tal.

Main Bol Ending Phrases

A small, but important feature of kaydas is the ending phrase of the main bol (the end of each half). Almost all kaydas will end with one of the pairs below, or a similar one:

- tuna/dhinna

- tinna/dhinna

- tuna kata/dhinna kata

- tinna kata/dhinna kata

- tinna kina/dhinna gina

- tina taka/dinna taka

- tin-na- kitataka/dhin-na- kitataka

Notice that every example includes the open stoke tin (or its alternate syllable tu) followed by na. This type of phrase at the end of the main bol is one of the distinctive features of the kayda. Very few kaydas do not have it.

Our beginner’s kayda above ends with the first pair:

And all of the Dilli kaydas we have looked at end with tinna kina/dhinna gina, the most common ending for Dilli kaydas.

These phrases are important because they help to shape the overall stress pattern, or "melody", in the composition. As we will see below, the kayda’s rise-and-fall pattern usually begins, and ends, with these phrases.

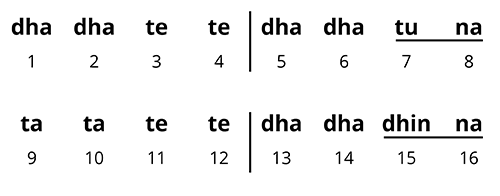

The khali section begins with the ending phrase of the first half

If you read the last section, then you might have noticed that these ending phrases are tali-khali counterparts; the one at the end of the first half is the khali version (closed), and the one at the end of the second half is the tali version (open).

So the khali section of most kaydas will usually begin with this ending phrase of the first half, and then lead into the main khali section in the second half.

The underlined section below shows this rise in intonation:

This rise in tension is then resolved in the final section, particularly in the ending phrase, the tali counterpart to the first ending phrase.

Listen again to this kayda and pay attention to the intonation of the ending bols tuna and dhinna:

Listen to any of the kaydas on this website, both spoken and played, and you should hear this same melody (it is easiest to hear at medium and faster speeds).

I should note that there are some exceptions to these ending phrases of kaydas. Sometimes they are not made from tali-khali counterparts, but are the same in each half. And a small number of kayda may not include these traditional-type endings.

Also, not all speakers will have a noticeable rise in the intonation of their voice for the khali section. But when you are familiar with the tali-khali bol system, you will still feel it.

Learning Kayda Phrases

To truly appreciate even a simple kayda, you need to hear more than just the main phrases. You need to hear the smaller bols and how they relate to each other.

Tabla students, of course, will be learning the language as they learn to play. For listeners, however, picking up the language is more challenging.

The best, and fastest way to do this is to learn to speak some kaydas. Not just read, but speak. Then listen closely to demonstrations which are performed at a speed that you can follow.

The more you do both together, the more you will pick up the language. But listening without speaking will take much longer, if it happens at all.

See the Kayda Overview sections

Some of the kaydas on this website will have guides to the theme in their Overview sections (eventually). There you will find a discussion of the kayda’s phrases and divisions.

With the phrases and division in mind, listen closely to both the spoken and played demonstrations of the theme, and do your best to speak them with the same rhythm and cadences that you hear.

Pay Attention to Kayda Variations

Kaydas variations (discussed in the next section) use the same phrases of the theme, but in different arragements. This will help you identify the individual phrases and bols in a kayda, and broaden your understanding of how they can be combined.

References

Kippen, James. The Tabla of Lucknow – A Cultural Analysis of a Musical Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Misra, Chhote Lal. Tal Prabandh. New Delhi: Kanishka Publishers, 2006. (Hindi)

—. Tabla Granth. New Delhi: Kanishka Publishers, 2006. (Hindi)

Naimpalli, Sadanand. Tabla for Advanced Students. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan Pvt. Ltd., 2009.

Stewart, Rebecca Marie. The Tabla in Perspective. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, 1974.