Introduction to Classical Tabla

A South Asian Tradition

Spend a day in any North Indian city and chances are you’ll hear the sounds of the tabla.

It’s almost impossible not to. Whether coming from a music shop, a motor rickshaw’s stereo, or a temple, the tabla is everywhere.

Sometimes called “the king” of Indian drums, the tabla is the most well-known drum of North India. You’ll hear it in a broad range of musical styles and traditions, including classical, folk, devotional, and popular music, such as Bollywood film songs.

But above all, the most remarkable tabla tradition is the classical music known as Hindustani, or Shastriya Sangeet.

This classical tabla tradition is the subject of DigiTabla.

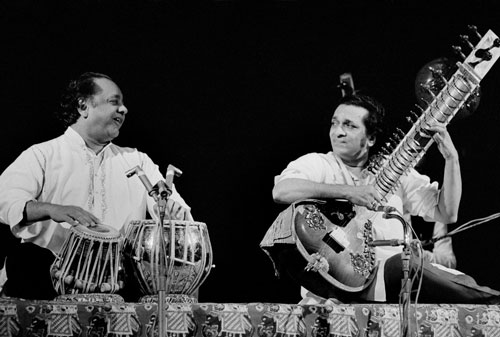

Alla Rakha (left) performing with Ravi Shankar at the Paris Jazz Festival, 1968 (courtesy Magnum Photos)

Classical Tabla Abroad

Of course, Indians need no introduction to classical Indian music or the tabla. But outside of South Asia, most people still understand very little about the music. And even less about the tabla.

This may seem surprising. Western popular culture first learned about classical Indian music back in the late 1960s, when the Beatles made Ravi Shankar and Alla Rakha famous (see photo above). And since that time, a steady stream of Westerners has been studying the music, both in India and the West.

In recent decades, there has also been a growing interest in so-called “World Music”, especially percussion. Latin, African, and Middle Eastern drums are now commonly studied and performed in the urban West.

Kids Learning the African Djimbe (courtesy Wikipedia)

Yet to this day, classical Indian tabla remains a mystery to most people outside of South Asia. This says a lot about how unusual, and how difficult, the tabla is.

But for people who learn something about the music, they often discover that it is well worth their time. Especially for those who like drumming and rhythm, the tabla often fascinates and amazes new listeners.

And for those who learn to play—myself included—the tabla sometimes becomes a life-long obsession.

The Wonder of Classical Tabla

The tabla is a hand drum. A pair of hand drums, to be specific. And at first glance, they look like a fancy pair of bongos with some funny black circles on the skins.

Tabla Pair

In the West, people often categorize the tabla as “World Percussion”, together with other popular hand drums, such as the conga, djembe, or darbuka.

But classical tabla has little in common with these traditions. In fact, the tabla has relatively little in common with any drumming tradition outside of South Asia.

With its clear bell-like tone, its highly intricate and expressive phrasings, and the sensuous inflections of the bass drum, the tabla sounds like no other drum.

And among hand drums, there is no other tradition which compares to the tabla’s depth, variety, and complexity, except for other Indian traditions such as the pakhawaj or the South Indian mrdangam.

But what is most remarkable about classical tabla is that the repertoire is primarily solo in nature; its compositions and improvisations are made mostly of independent phrases and patterns, and not repetitive rhythms or grooves.

A Solo Repertoire

Most often, you will hear classical tabla in accompaniment (tabla in vocal or instrumental music). But most of the classical tabla repertoire is performed only in tabla solo, or in practice in the manner of tabla solo.

Almost all of the compositions on this website are performed or practiced in tabla solo, from the simplest beginner kayda, to the most advanced gat or chakradar.

In other words, most of classical tabla is tabla solo.

And this is where classical tabla players will spend their formative years, if not most of their tabla lives: practicing in the mode of tabla solo, whether they are accompanists or not. In this sense, all tabla players are soloists.

Some of India’s most famous tabla players are, or were, primarily soloists. Some of them were not especially good accompanists, or never accompanied at all.

Ahmed Jan Thirakwa Khan, who many believe was the greatest tabla player of his generation, was known mostly as a soloist. Though he was also considered a fine accompanist, it was Thirakwa’s tabla solos that were so influential, and to which people still listen today.

Ahmed Jan Thirakwa Khan

This is perhaps classical tabla’s most remarkable achievement: a complete solo-percussion platform of astonishing complexity, variety, and depth, first created by mostly illiterate musicians sometime in the 1700s.

The Difficulty of Classical Tabla

Mickey Hart, drummer for The Grateful Dead and World Music pioneer, was interviewed by Peter Lavezzoli for his book The Dawn of Indian Music in the West. When asked what he found unique about the tabla’s approach, Hart said,

First it was the complexity, which was astounding. I couldn’t make heads or tails of it. Every other kind of rhythm, I could at least lock into and relate to. But with this, I didn’t have a physical relation to it, it was more of a mental thing. I couldn’t understand where the beginnings and endings were, where the phrases were. It was from another planet. (p. 90)

This quote captures a common experience for people who are new to the tabla: it is both fascinating and confusing at the same time. You feel that something really great is happening, but you’re not sure what it is.

This is the reality of classical tabla: it is not only difficult to understand, but also radically different from most other drumming traditions. And so there is little which can prepare you, even if you’re Mickey Hart.

Where to Begin?

This section of the website gives a general overview of the classical tabla tradition. But if you want to make any sense of the tabla’s music, then you need learn at least the basics of three things:

- The tabla’s syllables and patterns: bol

- The tabla’s performance environment: tal

- The most common compositional forms: kayda, rela, tukra, etc.

To do this, I recommend starting with the Listener’s Guide. This will also help you to navigate the other areas of the site.

Or if you are new to classical tabla, you may want to just listen first. YouTube now has a massive library of classical tabla recordings.

But no matter how many recordings you listen to, you won’t figure out much of classical tabla without guidance. For that, the best place to start is the Listener’s Guide.

Be patient. The tabla is worth it.

If you put some effort into learning a little about the three areas mentioned above, then you should begin to hear classical tabla. And when that happens, a surprisingly rich, elegant, funky, and complex drumming tradition will begin to reveal itself.

And once that happens, you might become a life-long fan. Because there’s absolutely nothing else on the planet like the tabla.

References

Lavezzoli, Peter. The Dawn of Indian Music in the West. London: A&C Black, 2006.